Worm that jumps from rats to slugs to human brains has invaded Southeast US

Multiple rats in Atlanta test positive for calamitous, rapidly spreading parasite.

The dreaded rat lungworm—a parasite with a penchant for rats and slugs that occasionally finds itself rambling and writhing in human brains—has firmly established itself in the Southeast US and will likely continue its rapid invasion, a study published this week suggests.

The study involved small-scale surveillance of dead rats in the Atlanta zoo. Between 2019 and 2022, researchers continually turned up evidence of the worm. In all, the study identified seven out of 33 collected rats (21 percent) with evidence of a rat lungworm infection. The infected animals were spread throughout the study’s time frame, all in different months, with one in 2019, three in 2021, and three in 2022, indicating sustained transmission.

Although small, the study “suggests that the zoonotic parasite was introduced to and has become established in a new area of the southeastern United States,” the study’s authors, led by researchers at the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, concluded. The study was published Wednesday in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

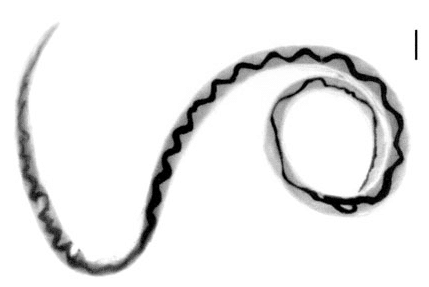

The finding is concerning given the calamitous infection the rat lungworm, aka Angiostrongylus cantonensis, can cause in humans. The parasitic nematodes are, as their name suggests, typically found in rats. But they have a complicated life cycle, which can be deadly when disrupted.

The study involved small-scale surveillance of dead rats in the Atlanta zoo. Between 2019 and 2022, researchers continually turned up evidence of the worm. In all, the study identified seven out of 33 collected rats (21 percent) with evidence of a rat lungworm infection. The infected animals were spread throughout the study’s time frame, all in different months, with one in 2019, three in 2021, and three in 2022, indicating sustained transmission.

Although small, the study “suggests that the zoonotic parasite was introduced to and has become established in a new area of the southeastern United States,” the study’s authors, led by researchers at the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, concluded. The study was published Wednesday in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The finding is concerning given the calamitous infection the rat lungworm, aka Angiostrongylus cantonensis, can cause in humans. The parasitic nematodes are, as their name suggests, typically found in rats. But they have a complicated life cycle, which can be deadly when disrupted.

Sickening cycle

Normally, adult worms live in the arteries around a rat’s lungs—hence rat lungworm. There, they mate and lay eggs. The worm’s larvae then burst out of the lungs, get coughed up by the rat, and are swallowed and eventually pooped out. From there, the larvae are picked up by slugs or snails. This can happen if the gastropods eat the rat poop or if the ravenous larvae just bore into their soft bodies. The larvae then develop in the slugs and snails, which, ideally, are eventually eaten by rats. Back in a rat, the late-stage larvae penetrate the intestines, enter the bloodstream, and migrate to the rat’s central nervous system and brain. There they mature into sub-adults then migrate to the lungs, where they become full adults and mate, thus completing the cycle.

Humans become accidental hosts in various ways. They may eat undercooked snails or inadvertently eat an infected slug or snail hiding in their unwashed salad. Infected snails and slugs can also be eaten by other animals first, like frogs, prawns, shrimp, or freshwater crabs. If humans then eat those animals before fully cooking them, they can become infected.

When a rat lungworm finds itself in a human, it does what it usually does in rats—it heads to the central nervous system and brain. Sometimes the migration of the worms to the central nervous system is asymptomatic or only causes mild transient symptoms. But, sometimes, they cause severe neurological dysfunction. This can start with nonspecific symptoms like headache, light sensitivity, and insomnia and develop into neck stiffness and pain, tingling or burning of the skin, double vision, bowel or bladder difficulties, and seizures. In severe cases, it can cause nerve damage, paralysis, coma, and even death.

It’s often thought that the worm can’t complete its life cycle in humans and that it ends up idly wandering around the brain for a month or two before it’s eventually killed off by immune responses. However, there has been some evidence of adult worms reaching the human lungs. Regardless, there’s no specific treatment for a rat lungworm infection. No anti-parasitic drugs have proven effective, and, in fact, there’s some evidence they can make symptoms worse by spurring more immune responses to dying worms. For now, supportive treatment, pain medications, and steroids are typically the only options.

Humans become accidental hosts in various ways. They may eat undercooked snails or inadvertently eat an infected slug or snail hiding in their unwashed salad. Infected snails and slugs can also be eaten by other animals first, like frogs, prawns, shrimp, or freshwater crabs. If humans then eat those animals before fully cooking them, they can become infected.

When a rat lungworm finds itself in a human, it does what it usually does in rats—it heads to the central nervous system and brain. Sometimes the migration of the worms to the central nervous system is asymptomatic or only causes mild transient symptoms. But, sometimes, they cause severe neurological dysfunction. This can start with nonspecific symptoms like headache, light sensitivity, and insomnia and develop into neck stiffness and pain, tingling or burning of the skin, double vision, bowel or bladder difficulties, and seizures. In severe cases, it can cause nerve damage, paralysis, coma, and even death.

It’s often thought that the worm can’t complete its life cycle in humans and that it ends up idly wandering around the brain for a month or two before it’s eventually killed off by immune responses. However, there has been some evidence of adult worms reaching the human lungs. Regardless, there’s no specific treatment for a rat lungworm infection. No anti-parasitic drugs have proven effective, and, in fact, there’s some evidence they can make symptoms worse by spurring more immune responses to dying worms. For now, supportive treatment, pain medications, and steroids are typically the only options.

Uncontrolled spread

For all of the above reasons, prevention and control of rat lungworm are seen as critical. That’s why its sustained foothold in the US is alarming. Rat lungworm has turned up in the Southeastern US before, but cases have been sporadic and have not been seen before in Georgia rats. Previously, the parasite has been caught infecting captive nonhuman primates in Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and Alabama, and a red kangaroo in Mississippi. In 2018, a study led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified reports of six cases in humans between 2011 and 2017, which could not be explained by travel (four in Texas and one each in Tennessee and Alabama).

It seems, though, that this mind-marauding worm is quietly building up its numbers and invading new continents and territories—in addition to central nervous systems. The rat lungworm parasite was first described in Canton (Guangzhou), China, in 1935 and, for decades after, was considered limited to disease-endemic areas of the Pacific basin and Southeast Asia. But, with climate change and the human-facilitated spread of rats and other hosts, especially giant snails, rat lungworm is rapidly emerging around the globe. It’s now found in parts of Africa, the Caribbean, and North America. Human cases have now been reported from 30 territories. (A relative of A. cantonensis, A. costaricensis, is also found in Latin America.)

In 2017, Hawaii reported a boom in human infections with rat lungworm, which was linked to the rise of an invasive “semi slug” that is particularly good at picking up the parasite. Hawaii ultimately tallied 18 confirmed and three probable human cases that year, a dramatic increase from previous years. A decade earlier, in 2007, the state recorded only two cases.

Rat lungworm’s latest frontier is Europe. Up until 2018, the parasite was not considered endemic to the region. But, that year, worms popped up in hedgehogs on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca. And, earlier this year, researchers reported that it had established a foothold in the city of Valencia on the Spanish mainland.

It seems, though, that this mind-marauding worm is quietly building up its numbers and invading new continents and territories—in addition to central nervous systems. The rat lungworm parasite was first described in Canton (Guangzhou), China, in 1935 and, for decades after, was considered limited to disease-endemic areas of the Pacific basin and Southeast Asia. But, with climate change and the human-facilitated spread of rats and other hosts, especially giant snails, rat lungworm is rapidly emerging around the globe. It’s now found in parts of Africa, the Caribbean, and North America. Human cases have now been reported from 30 territories. (A relative of A. cantonensis, A. costaricensis, is also found in Latin America.)

In 2017, Hawaii reported a boom in human infections with rat lungworm, which was linked to the rise of an invasive “semi slug” that is particularly good at picking up the parasite. Hawaii ultimately tallied 18 confirmed and three probable human cases that year, a dramatic increase from previous years. A decade earlier, in 2007, the state recorded only two cases.

Rat lungworm’s latest frontier is Europe. Up until 2018, the parasite was not considered endemic to the region. But, that year, worms popped up in hedgehogs on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca. And, earlier this year, researchers reported that it had established a foothold in the city of Valencia on the Spanish mainland.

Sounding the alarm

“[W]ith a foothold in Europe it could spread farther across the continent, potentially to more temperate regions, as has already occurred in Australia and the United States,” Spanish researchers warned. “Furthermore, as the climate warms, even more northern parts of Europe may become accessible to A. cantonensis, as seen in China.”

With the bleak outlook, it is “imperative that medical practitioners in Europe become more aware of this parasite and the diagnosis and treatment of the uncommon but potentially fatal disease it causes,” they conclude.

The researchers in Atlanta sound a similar alarm, calling for medical professionals in the Southern US to be aware of rat lungworm. They also call for more surveillance, genetic analysis, and modeling, which “is critical to mitigate risk to humans and other animals for infection.”

With the bleak outlook, it is “imperative that medical practitioners in Europe become more aware of this parasite and the diagnosis and treatment of the uncommon but potentially fatal disease it causes,” they conclude.

The researchers in Atlanta sound a similar alarm, calling for medical professionals in the Southern US to be aware of rat lungworm. They also call for more surveillance, genetic analysis, and modeling, which “is critical to mitigate risk to humans and other animals for infection.”